A tech company claims its AI technology can be used to spot active shooters.

In dozens of Nebraska schools, including Grand Island Senior High, paper hall passes have gone the way of slate boards, with digital hall passes taking their place.

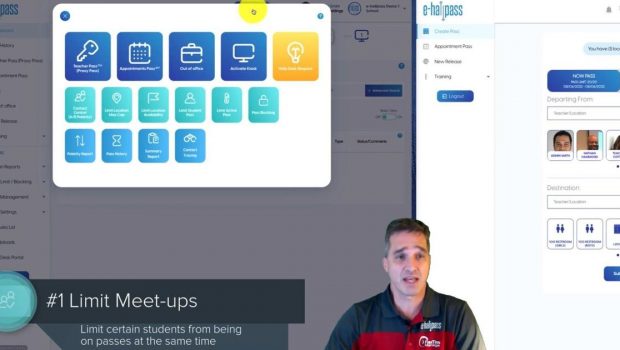

Digital — or contactless — hall passes allow students to request and be granted passes electronically. A teacher or administrator can approve or deny, and an app identifies where a specific student has permission to go, and for how long.

“E-hallpass is where educators run the halls, not students,” Nathan Hammond told The Independent in summing up the technology. Hammond is the executive director of Eduspire Solutions and developer of the e-hallpass software.

On its website, the company describes the software as, “A cloud-based contactless digital hall pass system that includes social distancing tools and has features that help limit mischief, meetups, vaping, vandalism, and much more.”

People are also reading…

Kearney Public High School and Fremont High School also use e-hallpass. Hammond said roughly 30 schools use the technology in Nebraska, while there are 3 million users nationwide.

Last summer Grand Island Senior High officials developed a needs analysis for the Grand Island Public Schools Board of Education, requesting the purchase of a subscription for e-hallpass.

The analysis, developed by a “student movement team” of administrators and students, stated, “We believe that implementing (e-hallpass) consistently building-wide as our sole pass system will increase student attendance rates as well as increase the overall safety of our building.”

The district purchased licenses for the software at $3 per student, totaling $8,100. The app does not require the purchase of additional equipment or infrastructure improvements.

Matt Wichman, principal of GISH’s Academy of Engineering and Technology, helped lead the team. At the October GIPS school board meeting, Wichman updated the board on e-hallpass, which was implemented soon after the beginning of the 2022-2023 school year. Considerations, Wichman told the board, included student referral data and “anecdotal concerns of staff.”

According to data provided to The Independent by GIPS, as of May 13 during the 2021-22 school year, there were 81 incidents of truancy and 532 times students were caught skipping class.

The same data set provided by GIPS shows 227 tardy violations.

“We recognized that we have an attendance issue,” said Jeff Gilbertson, GISH’s executive principal. “With that, a lot of student movement in the hallways, which the byproduct is tardiness to class.”

Watching hallway security camera footage played a role in implementing e-hallpass, Wichman said.

“We watched security camera footage just to see what movement truly looked like,” he said. “We looked at our discipline data at what point in the day. You can correlate the discipline with the movement and the traffic in the hallway.”

Using e-hallpass, GISH educators can determine how many and which students are — or should be — at a given location using a schoolwide dashboard.

“I can go on (the e-hallpass app) and see they were in the bathroom," said Wichman. "Then I can easily text one of my teachers that I know is on that side of the building and say, ‘Hey, can you see if so-and-so's there?’"

Kearney High School Assistant Principal Tyler Swarm said KHS uses e-hallpass for a similar purpose.

“With the paper pass system, a kid could get a pass to go to the nurse, go to the counseling office, but they didn't ever have to arrive there because the counseling office and nurse didn't know that they were expecting them to come.

“Now … we see a pass that has not arrived, the teacher sees it on their dashboard.”

Jackie Ruiz-Rodriguez is a senior at GISH and editor of the school’s student newspaper, The Islander and pens a column offering her perspective as a student for The Independent. She explained how the passes work.

“When the teacher accepts the pass, it gives you a timer. It times how much you're at the restroom, or you're at the library or your destination,” Ruiz-Rodriguez said. “They keep that in the records to see how much time you're spending out of class.”

If the student does not check back in before the timer runs out, the student is “flagged” in the system.

Ehallpass, GISH senior English teacher Marci Veach said, should not be mistaken with a tracking device, “pinging” where a student is located.

“I think there's a misconception; there's not a tracking device of any kind because it doesn't lead to red dots showing where they're at” in real-time.

Even so, said Fremont High School Principal Myron Sikora, his school has found sometimes paper-and-pen is the way to go.

If a parent shows up randomly, sometimes sending a student “runner” with a traditional pass reaches the classroom faster than a message from an app. Because of that, FHS has developed a hybrid hall pass system.

Fremont, which has used e-hallpass for three years, has about 1,480 students.

“We can send a pass (digitally), but if the teacher is in the middle of something, or is not able to immediately see that pass, then there's not necessarily a notification that that kid needs to come to the office,” Sikora explained. “So generally, when we've been sending passes from the office, we're still using a paper pass.”

Wichman said while still in the first semester of implementation at Grand Island Senior High, e-hallpass seemed to be making a difference. By November, “Our ninth and 10th grade attendance (was) 4% better, so 4% fewer kids are chronically absent.”

Hannah Quay-de la Vallee, senior technologist at the Center for Democracy & Technology, said schools often use digital hall passes in an effort to protect students, including from fights or using illicit substances.

“It’s really easy for that to drift into just adding discipline,” she added.

The Washington, D.C.-based center is a nonprofit working to ensure civil rights remain active in technology. Quay-de la Vallee said of e-hallpass: “This is a less invasive student monitoring system than some, but at the end of the day, it's still designed to monitor students.”

Hammond said, “There was a time when we were thinking, ‘Oh, we should do that (develop direct means of tracking).' Then you realize, school boards … parents don't really want that.”

Instead, “These controls allow schools to really be able to limit some of this congregating and mischief.”

Students who tend to fight with one another when in the same space can be kept apart. In the previously mentioned GISH data captured in May 2022, there were 44 occurrences of physical attacks “or fight(s) without a weapon.”

Kearney High School does not use that e-hallpass feature, said Swarm, the assistant principal.

“At this point, we haven't seen a lot of reason to set any of those limits. I'm sure that's a feature that could be utilized if we needed it,” he said. “The intention was … to make our building much more safe and secure from a movement standpoint and accountability standpoint, from going from place A to B.”

Kearney Public High School has roughly 1,550 students on-site, Swarm said. In school year 2021-2022, GISH had more than 2,500 students, as reported to the Nebraska Department of Education.

Teachers can override the e-hallpass system if there is an emergency, Wichman said.

“The teacher can always create a password (to) override it because the passes are actually generated by students,” he said. However, school administration can turn off the ability for a student to get passes.

School officials can limit who is in a specific area or identify who was in a specific area.

“For example, if there's a vandalism report, or some reason that we need to know who was out at certain times, we can pull all of that data,” Fremont’s Sikora said.

In Fremont, as well as other communities, besides being used for crowd control, digital hall passes allow educators to identify students who tend to violate school policy more than others might. Hammond said, teachers and administrators can “clip frequent fliers’ wings” to prevent the behaviors from happening again.

It can sometimes turn into a “good kid-bad kid” scenario, Quay-de la Vallee said, noting leeway could be given so-called “good kids.”

“Anytime we have machine, or technology, data being fed into a human decision, the human decision is still there. If you have that data now, and the administrator has more information about one student than another because they work more closely with that student,” she said, noting a hypothetical. “'There is an increase in fights, but you know, I know he's having a tough time.’ That’s not a problem that technology creates, but it can be a problem that technology exacerbates.”

Not having a specific purpose for collecting certain types of data amplifies this, Quay-de la Vallee said.

The Independent submitted a public records request asking for what categories of data are collected (“Data/Research Assessed”). Specifics regarding what data is collected were denied.

Justin Knight, GIPS’s legal counsel, said the district would not release additional documents because they are confidential under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

Cody Venzke, a senior counsel for Center for Democracy & Technology’s Equity in Civic Technology Project, said, “From a purely data ethics perspective, it's incredibly important that the people who are having data collected on them know what data is being collected, know how it's being used and know how they can exercise their rights over that data to have it deleted (or) to have it amended.”

Sometimes keeping track of simple information can create inferences.

Digital hall passes like e-hallpass can also allow educators to see the number of digital hall passes given to a student over a period of time.

“I have a student that is pregnant, and she needs to go to the bathroom more, which is a totally medical issue,” Gilbertson said.

“Her teacher that came to me said, ‘We didn't know that until her requests went up.’”

There can be ethical concerns, Venzke said.

“What are actually the ethical considerations of having a teenager, a young adult, having this personal information about their lives being algorithmically identified by technology, as opposed to a trusted adult? There's a deeper question of what do you do with that information as an institution? Are you supporting the student, or are you prosecuting the student?” he said. “If you want to create an environment where students can learn, and feel safe and feel welcome, you have to lean into that. And there's not very many spots where surveillance through technological means is really furthering students and learning and growth as adults.”

Ehallpass is going well at Kearney High, Swarm said, despite students being skeptical initially.

“From our admins’ position, I think it's going phenomenal."

Gilbertson and Wichman spoke to the Independent soon after an active shooter lockdown drill at GISH – which Gilbertson called a “pretty intense scenario.”

Typically, he explained, some staff members sweep the hallways, making sure students are where they should be if what was once unthinkable happens.

It can be a “teaching moment,” Gilbertson said, “coaching adults and students who are loose in the hallways during the drill.”

The drill run using e-hallpass was different from past drills, school officials agreed during the drill’s debriefing, Gilbertson said.

There were far fewer people loose in the hallways following the drill using e-hallpass.

“We minimized that to a trickle. I saw one student, personally.”

Gilbertson said it’s no longer a matter of hoping an act of mass violence doesn’t occur at high schools.

“No, we're talking about when it happens. This is how we're going to save lives.”

Jessica Votipka is the education reporter at the Grand Island Independent. She can be reached at 308-381-5420.

Gloss