How technology has changed the way we tell stories

Stories connect us. They enrich, they contextualize, they shape and inform the world around us. They spark social movements.

And for 140 years, The Gazette has told the stories of Iowans, recently like that of the Westerns, a Black family that’s farmed in Iowa for 158 years, making theirs likely the only one of about 1,700 Iowa Heritage Farms owned by a Black family.

Or of Johnny Ray Delgado and his girlfriend, Mary Sand, part of a growing population of homeless individuals in Linn County living outdoors, a population that has more than tripled since summer 2019.

One Gazette reader said that article and its pictures make the unseen seen.

“The large color photo of Johnny Ray Delgado and Mary Sand is beautiful and heartbreaking,” wrote Gretchen Reeh-Robinson of Mount Vernon. “Delgado and Sand are living in a tent in ‘a little-known village of homeless people’ in Cedar Rapids. Elijah Decious writes to make ‘homeless people’ real, and their front page presence brings them inside our homes.”

How those stories are told and reported has changed dramatically over the decades — more so over the last 20 to 30 years — with the rise of 24-hour news channels, the internet, social media and digital technology shifting storytelling to a more all-encompassing experience, said Roy Peter Clark, who has taught writing at The Poynter Institute, a Florida nonprofit dedicated to media studies, to students of all ages since 1979.

“Stories enrich our experience,” Clark said.

The Gazette’s storytelling process

Story is and has always been an integral part of the human experience, he continued. And while research suggests the global attention span is narrowing due to the amount of information that is presented to the public, people still are interested in a good story, as evidenced by the rise and popularity of long-form conversation podcasts and complex, binge-worthy docuseries on streaming services and the lure of long-form journalism online, Clark said.

For The Gazette, that’s meant delving into podcasts, and developing interactive maps, graphics and timelines as well as videos and short, daily newscasts to enhance visual storytelling, said Executive Editor Zack Kucharski.

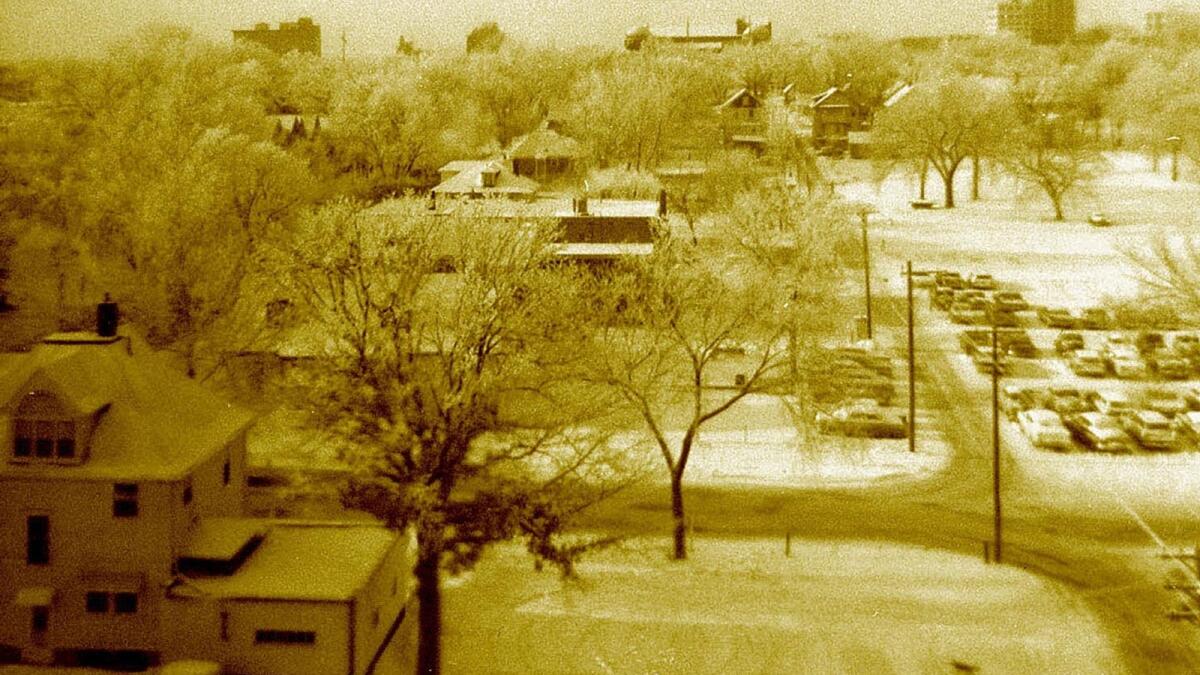

He pointed to the paper’s coverage of the 2008 flood, the 2020 derecho and its series on Little Mexico, a Cedar Rapids neighborhood razed in the 1960s to build Interstate 380. The projects combined aerial drone photography, historical maps and photos and videos to create interactive maps and short documentaries.

“You used to have to touch and hold a big newspaper,” Kucharski said. “Well, now most people that are accessing our website are doing it from their smartphone. And so how you prepare stories and how you think about the information that you want to share is different.

“You're watching the short-term videos, and those YouTube shorts are immensely popular,” he said. “The newspaper that's known for context has to find ways to weave all of that information into a tighter attention span, because our readers are competing for time.”

News reporters changing with the times

Reporters, too, have had to adjust as different technologies come online.

Rod Boshart formerly managed The Gazette's Des Moines Bureau, covering the Iowa Legislature, state government and politics until his retirement in 2021. During his roughly 40-year career, he went from dictating stories from the campaign trail over the phone to editors to filing stories on a laptop.

“It was a gradual, step-by-step from typewriter to Radio Shack laptops,” which would show only five lines of text and required connecting an acoustic coupler to the phone's receiver and pressing “send.” Copytakers on the news desk would put their phone into another acoustic coupler linked to a computer. The laptop’s modem would then read the report and convert every character typed into a beep, similar to Morse code, and the computer at the news desk would then convert and upload the text.

Rod Boshart, then the manager of The Gazette’s Des Moines Bureau, listens to Iowa House Speaker Pat Grassley while interviewing him Dec. 19, 2019, in Grassley’s office at the Capitol in Des Moines. (The Gazette)

Then came the internet, smartphones and social media, leading to the rise of an instantaneous, never-ending news cycle.

In 2017, when former Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad resigned to become U.S. ambassador to China, Boshart found himself faced with utilizing new skills and new technology he never thought he would have to use to tell the story of Branstad’s historic 22-year, five-month run as the longest-serving governor in U.S. history.

Boshart, the longtime dean of Iowa Statehouse reporters who began his career as a reporter for the United Press International wire service, drove with an intern to Branstad’s hometown of Leland, where the intern shot photos of the family farm where Branstad grew up and downtown Leland. Boshart compiled audio and video clips of the former governor’s old law partner and others to help tell the story of the farm boy-turned-political icon.

While routine for reporters today — who grew up with cellphones and smartphones in their pockets that are now equipped with 12-megapixel ultra wide and telephoto lenses and capable of shooting and editing high-definition video — it was a large departure for the traditional, shoe-leather reporter.

Boshart recalled the contrast with a story he wrote just a few years before about Robert D. Ray’s archives offering a rare look into the former Iowa governor's tenure. It was more of a traditional, straightforward news story that included a chronology and collection of photos of Ray’s time as Iowa's chief executive from 1969 to 1983.

With the Branstad story, Boshart saw the incorporation of audio and video clips as a “new way to look at (the story) in a different way, and I thought it was effective.”

“I think it’s better storytelling,” Boshart said. “It was multidimensional and almost like being … a broadcast (radio), video and a print reporter all in one.”

While time consuming to do all that, “it made you think differently about how you approached (the story) since you didn’t before worry about what something looked like or sounded like,” Boshart said. “It was forcing an old dog to learn new tricks.”

The end result, though, he said, could not be argued with.

“With a newspaper story, you can paint a picture, but this … I thought it was a really effective way to communicate a story and bring it to life,” Boshart said. “It was both exciting, but also challenging and frustrating in some ways.”

And while the mode of reporting has “exponentially improved,” the mechanics and basics of writing and formulating a story is the same as the first journalism school class he took in 1979, Boshart said.

“They've helped in the reporting process,” The Gazette’s Kucharski said of new digital technology. “I think the majority of the staff now wonders what it would have been like to report pre-Google and internet days. And so, you know, the process of news gathering has changed, and that's going to continue to happen.”

Newsrooms using social media

University of Iowa Professor David Dowling studies digital media and technology. His research focuses on digital journalism’s pivot toward increasingly immersive forms of storytelling — from podcasts to virtual reality and interactive documentaries.

“I think, to some extent, if you get into a medium like podcasting, you're going to feel a lot more vulnerability by the reporter,” Dowling said. “You'll feel a lot more of their presence in the story. Just listen to Michael Barbaro (on the New York Times’ “The Daily” news podcast). His halting delivery has been parodied wonderfully by “Saturday Night Live" and other places. But to be sure, there’s something extraordinary about that (which others are now mimicking). And that is a humanized reporter that can actually play a role in the story and be in a story, but not interfere with it and ruin it, but to actually make it more transparent, more honest and more fair, which is more deeply contextualized and richly analyzed, which is really the goal of higher quality news.“

Social media, as well, has become an invaluable tool for newsrooms to generate story ideas, monitor news, track trends, engage with readers and brand and distribute content to different audiences.

“A lot of people will throw up their hands and say, ‘Oh, the sky is falling. Social media has polarized us (and) created so much hate speech, etc.,’ ” Dowling said. “And it’s very easy to point to the downsides and the drawbacks of social media leading the news cycle. Frankly, we can see the problems with that. But the other side of the coin is … conscientious and thoughtful, mindful, intentional — slow even. Surveying of the media landscape through social media can lead to incredibly effective agenda setting for any news organization.”

He pointed to Unicorn Riot as a “poster child” for the use of social media and reporting.

The nonprofit media collective came to prominence in May 2020, in the course of protests over the killing of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis. Founded by a group of journalists dissatisfied with traditional media coverage of protests against racial injustice and police shootings of Black people, the collective sought to provide an alternative mode of protest coverage.

“They used social media the best to cover the (Black Lives Matter) protests of any news organization,” Dowling said. “I'm not alone in saying that. The New York Times said it. The Washington Post said it. … It's because they put the mic in the hands of people in the community, and they let them speak for themselves. … So they didn't go to the police or government officials who have a giant voice already.”

He said it showed “powerful journalism” that lacks an authentic, community voice “doesn't have legs, doesn't have traction, without social media.”

Newsroom fundamentals have not changed

Kucharski, though, stressed that the fundamentals of reporting and storytelling — accuracy, objectivity, context, relevance, succinctness and impact — have not changed.

"It's just adapting to use the new technology, use the new tools available,“ he said. ”The tried and true things still work. There's a method to all of them. Sometimes it's just coming up with the new flavor or understanding. How do we apply some of that, the logic or the critical thinking, while incorporating that technology?

“ … You still have to sort through and figure out what is good information. This organization has done it for 140 years, and we will continue to do that going forward. … And we'll work hard to figure out how to ethically and responsibly incorporate that into what we do each day.”

Comments: (319) 398-8499; tom.barton@thegazette.com

Gloss