Privacy, Cybersecurity and Access to Beneficial Ownership Information: FinCEN Issues Notice of Proposed Regulations Under the Corporate Transparency Act | Ballard Spahr LLP

A Deep Dive Into FinCEN’s Latest Proposals Under the CTA

On December 16, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) issued a 54-page notice of proposed rulemaking (“NPRM”) regarding access by authorized recipients to beneficial ownership information (“BOI”) that will be reported to FinCEN under the Corporate Transparency Act (“CTA”). The CTA requires covered entities – including most domestic corporations and foreign entities registered to do business in the U.S. – to report BOI and company applicant information to a database created and run by FinCEN upon the entities’ creation or registration within the U.S. This database will be accessible by U.S. and foreign law enforcement and regulators, and to U.S. financial institutions (“FIs”) seeking to comply with their own Customer Due Diligence (“CDD”) compliance obligations, which requires covered FIs to obtain BOI from many entity customers when they open up new accounts.

In regards to this NPRM, FinCEN’s declared goal is to ensure that

(1) only authorized recipients have access to BOI; (2) authorized recipients use that access only for purposes permitted by the CTA; and (3) authorized recipients only redisclose BOI in ways that balance protection of the security and confidentiality of the BOI with furtherance of the CTA’s objective of making BOI available to a range of users for purposes specified in the CTA.

Further, FinCEN has indicated that, “[c]oincident with the protocols described in this NPRM, FinCEN is working to develop a secure, non-public database in which to store BOI, using rigorous information security methods and controls typically used in the Federal government to protect non-classified yet sensitive information systems at the highest security levels.”

The comment period for the NPRM is 60 days. The NPRM proposes an effective date of January 1, 2024, consistent with when the final BOI reporting rule at 31 C.F.R. § 1010.380 becomes effective. The proposed BOI access regulations will be set forth separately at 31 C.F.R. § 1010.955, rather than existing 31 C.F.R. § 1010.950, which governs the disclosure of other Bank Secrecy Act (“BSA”) information.

This NPRM relates to the second of three sets of regulations which FinCEN ultimately will issue under the CTA. As we have blogged (here and here), FinCEN already has issued proposed (but not final) regulations regarding the BOI reporting obligation itself. FinCEN still must issue proposed regulations on “reconciling” the new BOI reporting regulations and the existing CDD regulations applicable to covered FIs for obtaining BOI from their own entity customers.

As we discuss, the lengthy NPRM suggests answers to some questions, but it of course also raises other questions. Although domestic and even foreign government agencies will have generally broad access to the BOI database, assuming that they satisfy various requirements, the NPRM’s proposed access for FIs to the BOI database is relatively limited.

Access to the BOI Database

The CTA authorizes FinCEN to disclose BOI to five categories of recipients:

- Federal, State, local and Tribal government agencies;

- Foreign law enforcement agencies, judges, prosecutors, central authorities, and competent authorities;

- FIs using BOI to facilitate compliance with their own CDD requirements and who have received the reporting company’s prior consent;

- Federal functional regulators and other appropriate regulatory agencies acting in a supervisory capacity assessing FIs for compliance with CDD requirements; and

- U.S. Department of Treasury, which has “relatively unique access” to BOI tied to an officer or employee’s official duties requiring BOI inspection or disclosure, including – importantly – for tax administration.

Generally, the CTA expressly restricts access to BOI to only those authorized users at a requesting agency: (1) who are directly engaged in an authorized investigation or activity; (2) whose duties or responsibilities require access to BOI; (3) who have undergone appropriate training or use staff to access the system who have undergone appropriate training; (4) who use appropriate identity verification to obtain access to the information; and (5) who are authorized by agreement with the Secretary to access BOI. The CTA also requires each requesting agency to establish and maintain a secure system to store BOI, establish privacy and data security protocols, certify compliance to FinCEN on an initial and then semi-annual basis, and conduct an annual audit, available to FinCEN on request, as to proper access, use and maintenance of BOI. (To read our blog post on a recent European Union court decision striking down public access to BOI, see here.)

FinCEN will retain sole discretion to decline to provide BOI to any requesting agency or FI that fails to comply with any requirement under the proposed regulations, or if the information is being requested for an “unlawful purpose,” or if “other good cause exists to deny the request.” FinCEN also may suspend or debar requesters. The NPRM reiterates the statutory penalties for violating the CTA, which include up to $500 a day for each civil violation, as well as up to five years in prison for a criminal violation, or up to 10 years in prison for an “aggravated” violation.

Federal, State, Local and Tribal government agencies

The NPRM provides that FinCEN may disclose BOI to agencies engaged in national security, intelligence or law enforcement if the BOI is for use in furtherance of such activities. These agencies will have broad access to the BOI database and will be able to conduct searches using multiple search fields.

Federal agency access will be “activity-based.” Accordingly, the NPRM proposes that an agency that is not traditionally understood as a “law enforcement” agency, such as a Federal functional regulator, nonetheless may receive BOI because “law enforcement activity” may encompass civil law enforcement by the agency, including civil forfeiture and administrative proceedings. Such agencies would include the Securities and Exchange Commission and other regulatory agencies.

FinCEN also may disclose BOI to State, local and Tribal law enforcement agencies if “a court of competent jurisdiction” has authorized the law enforcement agency to seek the BOI in a criminal or civil investigation. The NPRM does not define what it means for a court to “authorize” such disclosure, and seeks input on whether it should include state or local grand jury subpoenas, which sometimes, depending on the jurisdiction, can be signed by a prosecutor, not a court.

Federal government agencies requesting access to the BOI database will have to submit brief justifications to FinCEN for their searches, and these justifications will be subject to oversight and audit by FinCEN under future guidance that FinCEN will issue. State, local and Tribal and law enforcement agencies will be required to upload the court document authorizing the agency to seek BOI from FinCEN, which will review the authorization for sufficiency before approving. Every domestic agency seeking BOI will need to enter into a memorandum of understanding, or MOU, with FinCEN before being allowed to access the database.

Foreign law enforcement agencies

Foreign requesters will not have direct access to the BOI database. Instead, they will submit their requests for BOI to Federal intermediary agencies, which will need to be identified. If the foreign request is approved, then the Federal agency intermediary will retrieve the BOI from the system and transmit it to the foreign requester. Federal agency intermediaries will need to ensure that they have secure systems for BOI storage and enter into MOUs with FinCEN. However, the NPRM proposes that FinCEN will directly receive, evaluate, and respond to BOI requests from foreign financial intelligence units.

The NPRM provides that a BOI request from a foreign requester would have to derive from a law enforcement investigation or prosecution, or from national security or intelligence activity, authorized under the foreign country’s laws. Foreign requests for BOI will need to be either requests made pursuant to an international treaty, agreement, or convention, or official requests by a law enforcement, judicial, or prosecutorial authority of a trusted foreign country where there is no international treaty, agreement, or convention that governs. The NPRM does not propose imposing any audit requirements on foreign requesters, but invites comments on that proposal.

FIs using BOI to comply with the CDD Rule

Access by FIs is more limited. The CTA authorizes FinCEN to disclose a reporting company’s BOI to an FI only to the extent that such disclosure facilitates the FI’s compliance with the CDD Rule, and only if the reporting company first consents. Each BOI request by a FI must be in writing and must certify that the request seeks to facilitate compliance with the CDD Rule, is made with the consent of the customer, and that the FI otherwise has complied with the CTA.

The NPRM interprets the phrase “financial institution subject to customer due diligence requirements under applicable law,” to mean that FIs may request access to the BOI database only when attempting to comply with the CDD rule. Although FinCEN is requesting comment on this proposal, this would mean that FIs may not request BOI access for other efforts to comply with the BSA, such as compliance with the related Customer Identification Program, or CIP, requirements – or, presumably, determining whether to file a Suspicious Activity Report. Likewise, this would mean that the many FIs subject to the BSA but not subject to the CDD Rule – such as money services businesses – never will have access to the BOI database.

Another important limitation on BOI access by FIs is that a FI, when attempting to comply with the CDD rule, may search only the consenting entity customer. Unlike government agencies, FIs cannot do multiple searches, such as searches building off of the results of prior searches. Moreover, FIs cannot do searches tied to individual beneficial owners – only to an entity. So, although an FI may be able to determine that X, Y and Z are the beneficial owners of Company A, a FI will not be able to determine if X is the beneficial owner of Companies A, B and C.

The NPRM contains another proposal that likely will frustrate FIs: BOI information can only be accessed by, or shared with, FI directors, officers, employees, contractors and agents physically within the U.S. This means that the offshore compliance teams maintained by many FIs will be rendered useless for CDD compliance if this proposal is included in the final regulations.

Each FI must develop and implement safeguards reasonably designed to protect the security, confidentiality and integrity of BOI received from FinCEN, consistent with procedures that the FI already has established to satisfy the requirements of section 501 of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (“GLBA”) in regards to protecting its customers nonpublic personal information. If the FI is not covered by the GLBA, then it must apply safeguards required under applicable Federal or State law and which are at least as protective as procedures that satisfy section 501 of the GLBA.

The NPRM does not address several other important questions involving FIs, such as: is a FI obligated to access the BOI database for purposes of CDD Rule compliance, or may it choose to do so? If the FI may choose, are there any rules regarding how that choice should be made? Further, what should an FI do if there is a discrepancy between the BOI it received from an entity customer under the CDD Rule and the BOI it receives from FinCEN under the CTA? As noted, FinCEN will issuing a third set of proposed regulations under the CTA regarding reconciling the CTA regulations and the existing CDD Rule, which presumably will involve expanding the obligations of the CDD Rule. Regardless, FinCEN may address these questions at that time.

Finally, there may be some contradictions between state law disclosure requirements for FIs in regards to individuals whose BOI has been submitted under the CDD Rule, and the prohibitions in the CTA and the NPRM regarding disclosure of BOI. This is a complex issue turning on the particulars of state law and potential exemptions, so we merely note the potential issue here.

Federal functional regulators supervising FIs for CDD Rule compliance

Federal functional regulators generally will have limited access to the database if requesting BOI for the purpose of ascertaining CDD compliance by a supervised FI. The NPRM identifies these regulators as the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Federal Reserve System, the National Credit Union Administration, and the Commodities Futures Trading Commission.

The NPRM states that FinCEN is still developing this access model and accompanying functionality, but expects federal functional regulators to be able to retrieve any BOI that the FIs they supervise received from FinCEN during a particular period, but not BOI that might reflect subsequent updates. Thus, regulators would receive the same BOI that FIs received for purposes of their CDD reviews. FinCEN expects that Federal functional regulators responsible for bringing civil enforcement actions also will be able to obtain BOI under the “activity-based” access permitted for “law enforcement,” described above. Finally, the NPRM proposes that financial self-regulatory organizations that are registered with or designated by a federal functional regulator pursuant to Federal statute – such as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or FINRA – may obtain BOI not directly from FinCEN, but instead from the FIs they supervise. The NPRM states that, “[w]ithout this level of access, these organizations would not be able to effectively evaluate an FI’s CDD compliance.” The NPRM refers to such organizations as SROs, and provides that they also may receive BOI from a Federal functional regulator for examination of CDD compliance by a supervised FI.

U.S. Department of Treasury

The NPRM states that “FinCEN envisions Treasury components using BOI for appropriate purposes, such as tax administration, enforcement actions, intelligence and analytical purposes, use in sanctions designation investigations, and identifying property blocked pursuant to sanctions, as well as for administration of the BOI framework, such as for audits, enforcement, and oversight.” Further, “FinCEN will work with other Treasury components to establish internal policies and procedures governing Treasury officer and employee access to BOI.”

The NPRM invites comments on the proposed scope of the term “tax administration.” This likely will be an important and controversial question, given the potential scope of IRS activity.

Verification of BOI

Verification of BOI is an important and thorny issue. FinCEN states that it “continues to evaluate options for verifying reported BOI. ‘Verification,’ as that term is used here, means confirming that the reported BOI submitted to FinCEN is actually associated with a particular individual.” This means that FinCEN is focusing on weeding out mismatches – intentional or unintentional – and fabricated persons. What FinCEN is not focusing on is ensuring that a listed, real person is actually a beneficial owner of the reporting entity (or, conversely, identifying true beneficial owners who have not been reported). Such a level of verification presumably would be incredibly resource-intensive and likely impossible on a broad scale.

This level of verification is equivalent to the verification obligations of FIs obtaining BOI from entity customers under the CDD rule: FIs do not have to verify that a listed person is in fact a beneficial owner of the entity, and instead may rely on the customer’s reporting form listing beneficial owners in the absence of any red flags to the contrary.

The fact that FinCEN will not undertake to verify BO status confirms that one of the primary functions of the CTA and the BOI database – and probably the primary function – is to serve as a source of information for downstream law enforcement and regulatory inquiries. That is, the database will not serve as a source of leads to initiate investigations, but instead will provide information once an investigation or inquiry into specific persons and entities already has begun.

FinCEN Identifiers for Entities

A FinCEN identifier is a unique identifying number that FinCEN will issue to individuals who have provided FinCEN with their BOI and to reporting companies that have filed initial BOI reports. The NPRM observes that the use of an intermediate company’s FinCEN identifier can create issues if a reporting company’s ownership structure involves multiple beneficial owners and/or intermediate entities. Thus, the NPRM proposes to permit a reporting company to use an intermediate entity’s FinCEN identifier only if the two entities have the same beneficial owners.

Specific Requests for Comment

The NPRM sets forth 30 specific requests for comment, under the six subheadings of (i) Understanding the Rule; (ii) Disclosure of Information; (iii) Use of Information; (iv) Security and Confidentiality Requirements; (v) Outreach; and (vi) FinCEN Identifiers.

Of particular interest, and consistent with the above discussion, the NPRM requests comments regarding the following issues:

- [C]omments discussing how State, local, and Tribal law enforcement agencies are authorized by courts to seek information in criminal and civil investigations . . . [and] whether there are any evidence-gathering mechanisms through which State, local, or Tribal law enforcement agencies should be able to request BOI from FinCEN, but that do not require any kind of court?

- Is requiring a foreign central authority or foreign competent authority to be identified as such in an applicable international treaty, agreement, or convention overly restrictive? If so, what is a more appropriate means of identification?

- Should FinCEN expressly define “customer due diligence requirements under applicable law” as a larger category of requirements that includes more than identifying and verifying beneficial owners of legal entity customers? . . . . It appears to FinCEN that the consequences of a broader definition of this phrase would include making BOI available to more FIs for a wider range of specific compliance purposes, possibly making BOI available to more regulatory agencies for a wider range of specific examination and oversight purposes, and putting greater pressure on the demand for the security and confidentiality of BOI.

- Could a State regulatory agency qualify as a “State, local, or Tribal law enforcement agency” under the definition in proposed 31 CFR 1010.955(b)(2)(ii)? If so, please describe the investigation or enforcement activities involving potential civil or criminal violations of law that such agencies may undertake that would require access to BOI.

- Because security protocol details may vary based on each agency’s particular circumstances and capabilities, FinCEN believes individual MOUs are preferable to a one-size-fits all approach of specifying particular requirements by regulation. FinCEN invites comment on this MOU-based approach, and on whether additional requirements should be incorporated into the regulations or into FinCEN’s MOUs.

- Are the procedures FIs use to protect non-public customer personal information in compliance with section 501 of Gramm-Leach-Bliley sufficient for the purpose of securing BOI disclosed by FinCEN under the CTA? If not, is there another set of security standards FinCEN should require FIs to apply to BOI?

Impact of the NPRM and Number of Entities with Access to the Database

The NPRM contains over 27 pages, under the heading of “Regulatory Analysis,” devoted to FinCEN’s analysis of the anticipated impact of the NPRM in regards to costs and benefits. This section contains a lot of numbers, purported cost/benefit discussions, and among other things, estimates of hours (of potentially dubious accuracy) that FIs will need to spend to establish the institutional safeguards, customer consents, written certificates and training necessary to comply with the regulations in order to access the BOI database as part of the FIs’ CDD rule compliance. This section is beyond the scope of this blog post. Instead, we simply will set forth two tables contained in the NPRM, which provide some clear and interesting statistics regarding the estimated number of private and public entities which will be accessing the database.

Here is Table 1, entitled “Affected Financial Institutions.” Recall that this table only pertains to FIs covered by the CDD rule, rather than all FIs subject to the BSA. The column entitled “Small Count” refers to FinCEN’s determination that most FIs are “small” entities, defined as having total annual receipts less than the Small Business Association (“SBA”) small entity size standard for the FI’s particular industry. For example, the SBA currently defines a commercial bank, savings institution or credit union as “small” if it has less than $750 million in total assets.

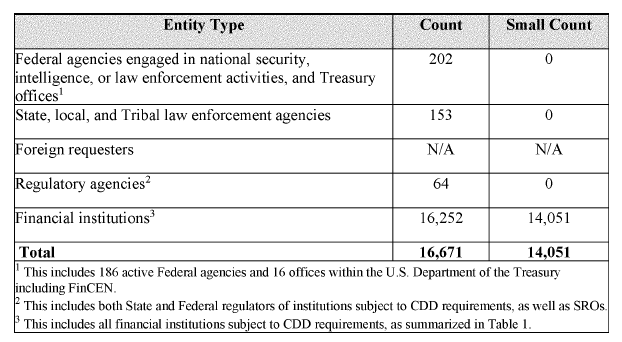

Here is Table 2, entitled “Affected Entities,” which includes government entities:

These tables underscore the paramount need for FinCEN to maintain very strong cybersecurity protections for the BOI database, which surely will be the target of would-be data breaches by bad actors (some of whom may perceive themselves as whistleblowers and white knights seeking information for global publication). There will be many points of access – i.e., points of potential vulnerability – for the database. As we previously blogged, the database will contain an enormous amount of information: FinCEN estimates that over 32 million initial BOI reports will be filed in the first year of the final regulations taking effect, and that approximately 5 million initial BOI reports and over 14 million updated reports will be filed every year thereafter.

These tables also underscore the daunting logistical hurdles facing FinCEN, a small agency, in the establishment and maintenance of the BOI database. As context, FinCEN notes in the NPRM that it currently fields approximately 13,000 inquiries a year through its Regulatory Support Section. But if only 10 percent of reporting companies have questions for FinCEN in the first year of the reporting requirement, FinCEN will face over three million inquiries.

[View source.]

Gloss