Loading Kernel Shellcode

In the wake of recent hacking tool dumps, the FLARE team saw a spike

in malware samples detonating kernel shellcode. Although most samples

can be analyzed statically, the FLARE team sometimes debugs these

samples to confirm specific functionality. Debugging can be an

efficient way to get around packing or obfuscation and quickly

identify the structures, system routines, and processes that a kernel

shellcode sample is accessing.

This post begins a series centered on kernel software analysis, and

introduces a tool that uses a custom Windows kernel driver to load and

execute Windows kernel shellcode. I’ll walk through a brief case study

of some kernel shellcode, how to load shellcode with FLARE’s kernel

shellcode loader, how to build your own copy, and how it works.

As always, only analyze malware in a safe environment such as a VM;

never use tools such as a kernel shellcode loader on any system that

you rely on to get your work done.

A Tale of Square Pegs and Round Holes

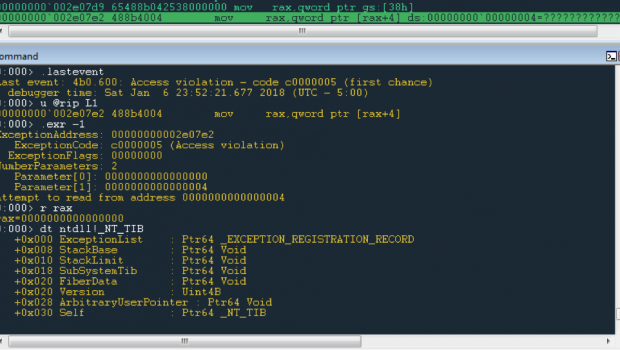

Depending upon how a shellcode sample is encountered, the analyst

may not know whether it is meant to target user space or kernel space.

A common triage step is to load the sample in a shellcode loader and

debug it in user space. With kernel shellcode, this can have

unexpected results such as the access violation in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Access violation from shellcode

dereferencing null pointer

The kernel environment is a world apart from user mode: various

registers take on different meanings and point to totally different

structures. For instance, while the gs segment register in 64-bit

Windows user mode points to the Thread Information Block (TIB) whose

size is only 0x38 bytes, in kernel mode it points to the Processor

Control Region (KPCR) which is much larger. In Figure 1 at address

0x2e07d9, the shellcode is attempting to access the IdtBase member of

the KPCR, but because it is running in user mode, the value at offset

0x38 from the gs segment is null. This causes the next instruction to

attempt to access invalid memory in the NULL page. What the code is

trying to do doesn’t make sense in the user mode environment, and it

has crashed as a result.

In contrast, kernel mode is a perfect fit. Figure 2 shows WinDbg’s

dt command being used to display the _KPCR type defined within

ntoskrnl.pdb, highlighting the field at offset 0x38 named IdtBase.

Figure 2: KPCR structure

Given the rest of the code in this sample, accessing the IdtBase

field of the KPCR made perfect sense. Determining that this was kernel

shellcode allowed me to quickly resolve the rest of my questions, but

to confirm my findings, I wrote a kernel shellcode loader. Here’s what

it looks like to use this tool to load a small, do-nothing piece of shellcode.

Using FLARE’s Kernel Shellcode Loader

I booted a target system with a kernel debugger and opened an

administrative command prompt in the directory where I copied the

shellcode loader (kscldr.exe). The shellcode loader expects to receive

the name of the file on disk where the shellcode is located as its

only argument. Figure 3 shows an example where I’ve used a hex editor

to write the opcodes for the NOP (0x90) and RET (0xC3) instructions

into a binary file and invoked kscldr.exe to pass that code to the

kernel shellcode loader driver. I created my file using the Windows

port of xxd that comes with Vim for Windows.

Figure 3: Using kscldr.exe to load kernel shellcode

The shellcode loader prompts with a security warning. After clicking

yes, kscldr.exe installs its driver and uses it to execute the

shellcode. The system is frozen at this point because the kernel

driver has already issued its breakpoint and the kernel debugger is

awaiting commands. Figure 4 shows WinDbg hitting the breakpoint and

displaying the corresponding source code for kscldr.sys.

Figure 4: Breaking in kscldr.sys

From the breakpoint, I use WinDbg with source-level debugging to

step and trace into the shellcode buffer. Figure 5 shows WinDbg’s

disassembly of the buffer after doing this.

Figure 5: Tracing into and disassembling

the shellcode

The disassembly shows the 0x90 and 0xc3 opcodes from before,

demonstrating that the shellcode buffer is indeed being executed. From

here, the powerful facilities of WinDbg are available to debug and

analyze the code’s behavior.

Building It Yourself

To try out FLARE’s kernel shellcode loader for yourself, you’ll need

to download the

source code.

To get started building it, download and install the Windows

Driver Kit (WDK). I’m using Windows

Driver Kit Version 7.1.0, which is command line driven, whereas

more modern versions of the WDK integrate with Visual Studio. If you

feel comfortable using a newer kit, you’re welcomed to do so, but

beware, you’ll have to take matters into your own hands regarding

build commands and dependencies. Since WDK 7.1.0 is adequate for

purposes of this tool, that is the version I will describe in this post.

Once you have downloaded and installed the WDK, browse to the

Windows Driver Kits directory in the start menu on your development

system and select the appropriate environment. Figure 6 shows the WDK

program group on a Windows 7 system. The term “checked build”

indicates that debugging checks will be included. I plan to load

64-bit kernel shellcode, and I like having Windows catch my mistakes

early, so I’m using the x64 Checked Build Environment.

Figure 6: Windows Driver Kits program group

In the WDK command prompt, change to the directory where you

downloaded the FLARE kernel shellcode loader and type ez.cmd. The

script will cause prompts to appear asking you to supply and use a

password for a test signing certificate. Once the build completes,

visit the bin directory and copy kscldr.exe to your debug target.

Before you can commence using your custom copy of this tool, you’ll

need to follow just a few more steps to prepare the target system to

allow it.

Preparing the Debug Target

To debug kernel shellcode, I wrote a Windows software-only driver

that loads and runs shellcode at privilege level 0. Normally, Windows

only loads drivers that are signed with a special cross-certificate,

but Windows allows you to enable

testsigning to load drivers signed with a test certificate. We can

create this test certificate for free, and it won’t allow the driver

to be loaded on production systems, which is ideal.

In addition to enabling testsigning mode, it is necessary to enable

kernel debugging to be able to really follow what is happening after

the kernel shellcode gains execution. Starting with Windows Vista, we

can enable both testsigning and kernel debugging by issuing the

following two commands in an administrative command prompt followed by

a reboot:

|

bcdedit.exe /set testsigning bcdedit.exe /set debug on |

For debugging in a VM, I install VirtualKD, but you can also

follow your virtualization vendor’s directions for connecting a serial

port to a named pipe or other mechanism that WinDbg understands. Once

that is set up and tested, we’re ready to go!

If you try the shellcode loader and get a blue screen indicating

stop code 0x3B (SYSTEM_SERVICE_EXCEPTION), then you likely did not

successfully connect the kernel debugger beforehand. Remember that the

driver issues a software interrupt to give control to the debugger

immediately before executing the shellcode; if the debugger is not

successfully attached, Windows will blue screen. If this was the case,

reboot and try again, this time first confirming that the debugger is

in control by clicking Debug -> Break in WinDbg. Once

you know you have control, you can issue the g command to let

execution continue (you may need to disable driver load notifications

to get it to finish the boot process without further intervention: sxd ld).

How It Works

The user-space application (kscldr.exe) copies the driver from a

PE-COFF resource to the disk and registers it as a Windows kernel

service. The driver implements device write and I/O control routines

to allow interaction from the user application. Its driver entry point

first registers dispatch routines to handle CreateFile, WriteFile,

DeviceIoControl, and CloseHandle. It then creates a device named

Devicekscldr and a symbolic link making the device name accessible

from user-space. When the user application opens the device file and

invokes WriteFile, the driver calls ExAllocatePoolWithTag specifying a

PoolType of NonPagedPool (which

is executable), and writes the buffer to the newly allocated

memory. After the write operation, the user application can call

DeviceIoControl to call into the shellcode. In response, the driver

sets the appropriate flags on the device object, issues a breakpoint

to pass control to the kernel debugger, and finally calls the

shellcode as if it were a function.

While You’re Here

Driver development opens the door to unique instrumentation

opportunities. For example, Figure 7 shows a few kernel callback

routines described in the WDK help files that can track system-wide

process, thread, and DLL activity.

Figure 7: WDK kernel-mode driver

architecture reference

Kernel development is a deep subject that entails a great deal of

study, but the WDK also comes with dozens upon dozens of sample

drivers that illustrate correct Windows kernel programming techniques.

This is a treasure trove of Windows internals information, security

research topics, and instrumentation possibilities. If you have time,

take a look around before you get back to work.

Wrap-Up

We’ve shared FLARE’s tool for loading privileged shellcode in test

environments so that we can dynamically analyze kernel shellcode. We

hope this provides a straightforward way to quickly triage kernel

shellcode if it ever appears in your environment. Download the source code now.

Do you want to learn more about these tools and techniques from

FLARE? Then you should take one of our Black Hat classes in Las Vegas

this summer! Our offerings include Malware

Analysis Crash Course, macOS

Malware for Reverse Engineers, and Malware

Analysis Master Class.

Gloss