Being a Professional at the Intersection of Tax and Technology

Why be a tax professional besides that it feels pretty darn good? First of all, it leaves me with time to ponder things more abstract, like gas taxes—and to write for Bloomberg Tax on such ponderings. And I’m a geek, to be sure, but I’m not the geekiest geek you’ve ever met. I haven’t written an operating system from scratch, and my programming skills are intermediate at best. But in the realm of tax, I’m as geeky as they get. I enjoy being able to pair my decidedly intermediate understanding of a lot of different technologies with my knowledge of tax and law to provide a perspective that might be missed by a writer who was all one or the other.

The world of tax is its own microcosm because taxes touch everything. It is less a unitary profession than a broad umbrella term for a group of professionals all milling about along the intersection of Tax Avenue and Technology Street, or Data Science Boulevard. There is a huge gathering at Tax Avenue and Accounting Court, and maybe a smaller one at the corner of Tax Avenue and Baseball Lane (but we’re here!). It is a field in which you can—and should—bring your own interests, background, and voices to ensure everything from policy to enforcement proceeds in light of the diversity of thought and views that it represents.

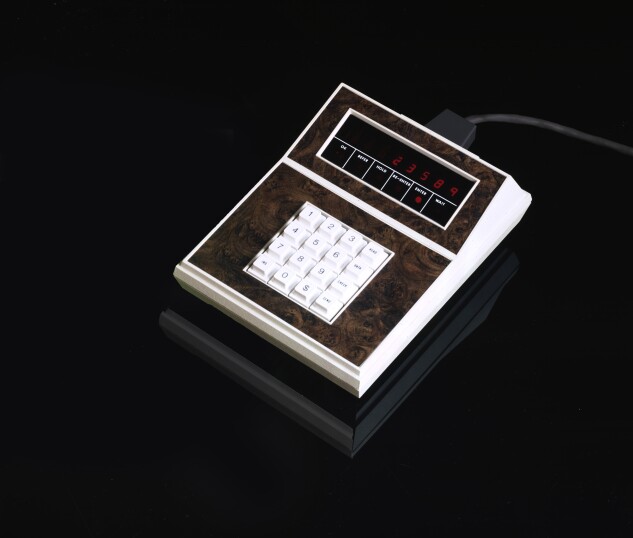

If I said I worked at the intersection of tax and technology, you’d likely envision one of two things: Either I continually answer the phone and inform a client that their cryptocurrency exchange doesn’t qualify as a 1031 exchange, or I’m deeply ensconced in the taxation of digital goods. I have indeed fielded phone calls similar to the former, and I do maintain an interest in the latter. But most of my day-to-day work deals with either retail establishments, point of sale systems (a cash register, essentially), and sales tax, or writing articles on how future electric vehicle development is being shaped by tax policy.

Of course this all makes sense, because I have a background in information technology and a pretty good understanding of mySQL databases.

Wait, what? Let’s back up.

The Tax and Tech Intersection: You’re Already There

Whenever you go into a retail establishment and pay for your meal or goods, you’re interfacing with a nuanced aspect of tax technology—the point-of-sale system. Every aspect of your transaction is recorded: items sold, taxable sales, total, change, etc. For many establishments, this is the canonical record of the business they have done, the sales taxes they have collected, and the taxes they are to remit to the state. This also will be the data used to substantiate income taxes owed, should there be a question. In other words: “I can’t have made $1 million last year; I only sold 15 hamburgers.”

Obviously, the database storing all of the transactions is pretty important. Most establishments must have redundant backups and cloud storage with encrypted images of their drives in off-site backups, organized chronologically, right? Let’s just say I am thrilled if I speak with a prospective client and they have a single backup separate from the working database in use in their establishment.

What stands between a business owner and fraud? The database, mostly. All the transactions are stored in there—cash, credit, gift card, freebies, all of it. If transactions could conveniently go missing, a fraudster might think a lot of tax overhead would disappear, and the collected sales tax could just be pocketed or put toward paying off the books staff. Sounds pretty simple, doesn’t it?

It’s Not That Simple

The best way to explain why just deleting a bunch of sales is simultaneously illegal and not a good idea is to illustrate how someone who did would be caught. First, after deciding to target the business, an undercover agent from the state department of revenue would show up unannounced, make a purchase in cash, ask for a receipt, and leave without issue. The DOR eventually would return, comb through the records, and look for their receipt in the database.

If the receipt isn’t there, the business owner has a problem—the owner will be presumed to be deleting cash sales and pocketing the paid sales tax. This is not good. If the receipt is there but its number doesn’t match in the database, the assumption is going to be that sales are being deleted, and the undercover DOR purchase was not among the deleted. This is also not good.

Finally, even if the receipt is there, the DOR is going to perform various other analyses on the data to get a sense of what they believe your total sales should be, multiply it by the average sale in the record you do have, slap on some fines and fees for fraud, and reassess the business. Reassessments for millions of dollars for small to midsize establishments are not uncommon.

If, as you read any of the above, you thought, “I can think of an alternative explanation for this anomaly that doesn’t involve fraud,” then you have just discovered my niche —and why tax needs more technologists.

Living in Tax Fraud SQL

Business owners generally treat point-of-sale systems like cash registers—they just want them to work, and they’ll bend their features to make them do what they want them to. They aren’t generally interested in what is going on under the hood—after all, the restaurateur went into the restaurant business, not IT.

Business owners sometimes use the live database for training new employees. Other times, databases crash, and business owners will tolerate an unbelievable amount of instability in their 25-year-old point of sale system that is running 25-year-old point of sale software on Windows XP Service Pack 1. There are a lot of reasons why a database may be corrupted or have wonky data that don’t necessarily entail a fraudster business owner.

That’s where people like me come in. We look at the database, look at the business owner, and elucidate for the DOR what it would take for the owner to accomplish the outcome they are suggesting. We look for what might really be going on with the underlying technology that gives the appearance of fraud without the intent.

More often than not, there are either no sales missing or sales missing because of a glitch in the hardware or software and not intentional fraud. Discovering that a series of gaps in the receipt scheme can be reproduced in the database by the system crashing when the fryer clicks on can mean the difference between a family continuing to operate their restaurant or closing their doors.

Helping them too keep those doors open, as a tax pro, feels pretty darn good.

This is a regular column from tax and technology attorney Andrew Leahey, principal at Hunter Creek Consulting and a sales suppression expert. Look for Leahey’s column on Bloomberg Tax, and follow him on Twitter at @leahey.

Gloss